Original Run: September 8, 2016

“I’m criminally Northern,” from black Twitter stalwart and cultural critic Jamilah Lemieux about the epic Tuesday night of black Southern intensity fueled by new TV shows Atlanta and Queen Sugar. Clearly, the Chicago native, who now calls New York City home, was not alone, as similar sentiments also showed up on Twitter. Those from the South or currently living la vida Southern also chimed in, amazed to see their lives represented so vividly and so uniquely on the small screen.

In name, the black South has shown up on television quite often in recent years. NBC’s sleeper hit comedy The Carmichael Show is set in Charlotte, N.C. Tyler Perry’s numerous series mostly take place in and around Atlanta. One could even argue that Perry’s success has been a gateway for more Atlanta on the small screen. House of Payne preceded the reality shows The Real Housewives of Atlanta and Love & Hip Hop: Atlanta as well as more respectable fare like Being Mary Jane andSurvivor’s Remorse.

But none of these shows are wholly invested in black Southern identity. Atlanta and Queen Sugarare, but not in a preachy or politically advancing manner. Instead, both shows are centered in a sense of place. And that specificity helps anchor each narrative, though they differ substantially. Having location as a bonus character enables both shows to dig deep and tell authentic stories that revolve around multidimensional characters that bear no resemblance to the caricatures we are so used to seeing. Consequently, these people feel not only like real people but like people you actually know or could be.

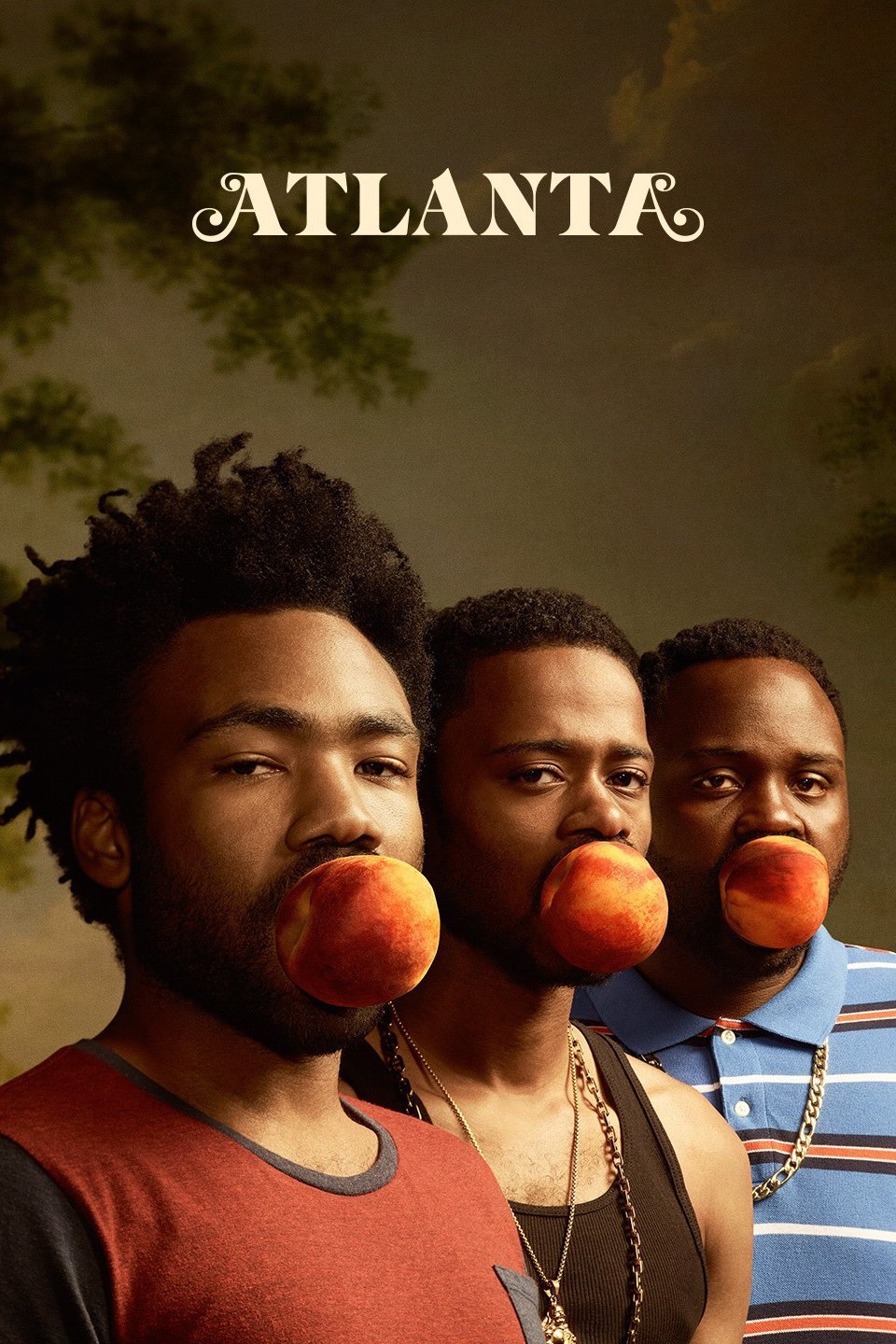

FX’s Atlanta, created by and starring Donald Glover, whose family moved to nearby Stone Mountain, Ga., when he was a kid, is probably not what most people, even his own fans, could have imagined. Even though Glover is also a rapper known as Childish Gambino, his FX show is largely a result of his work playing community college student and onetime-hotshot high school jock Troy Barnes on the long-running, quirky series Community, which debuted on NBC back in 2009.

Earn, Glover’s character, is living way beneath his Princeton potential and has run out of options until an underground single by his cousin Alfred (Brian Tyree Henry), who goes by Paper Boi, offers him new hope. The journey to manage his cousin’s budding career is far from a blinged-out tale of wannabe Love & Hip Hop: Atlanta vixens, VIP sections and expensive jewelry. Instead, it gets down and dirty.

It’s distinctively black and Southern. And that comes courtesy of the all-black writers who are brand-new to television, with the reported exception of Glover. They refreshingly abandon the disposable formula that has plagued far too many black-cast TV comedies. Atlanta digs deeper, going darker than most, while maintaining the weird and quirky vibe for which Glover is known.

Almost equally important, Atlanta challenges the concept of urban being just Northeastern, as in New York or Philadelphia, or Midwestern, as in Chicago or Detroit. Even though early Southern rappers like Memphis, Tenn., icons 8Ball & MJG and, later, Atlanta’s T.I., Jeezy and, now, Future have rapped and even boasted about the South’s mean streets, the perception of the South from the outside is still more about the KKK than an AK. For many of us, the hood is still the promised-land-turned-ghettos of places like Philadelphia, Newark, N.J., and Los Angeles. For some, Atlanta remains a haven, a way out of the grind of urban life. Maybe Atlanta is arguably a better existence for transplants than natives, but it is the hardships natives face that Atlanta addresses most.

If Atlanta reveals what a lot of us don’t think the South is, Ava DuVernay’s Queen Sugar is far more familiar terrain. But even as sophisticated as some of us have become in other parts of the country, Queen Sugar reminds us that there is still some good, i.e., a sense of family and community, in the rural South. Current Columbia professor Farah Jasmine Griffin wrote of the “symbolic, almost mythical sense of the South as home” in her 1995 book, “Who Set You Flowin’?”: The African-American Migration Narrative, and that’s what Queen Sugar, whose camera languishes on the beauty of the South, seizes upon.

This is exactly what DuVernay intends, but Queen Sugar is far from naively nostalgic. Adopted from Natalie Baszile’s 2014 novel, the hourlong drama, symbolically on Oprah Winfrey’s network OWN, tweaks the book’s original story, swapping out a mother-daughter tale for a more epic one centered on three siblings, while keeping the 800 acres of sugarcane that need farming after their father’s death at the fore.

Charley, the prodigal daughter of the Bordelon clan, played by newcomer Dawn-Lyen Gardner, breezes in from Los Angeles, on the heels of her professional basketball husband’s sex scandal, and pulls out numerous credit cards to make everything right. Nova, played by Rutina Wesley, is a journalist, who is away from her roots and in them at the same time. And then there is Ralph Angel, played by Kofi Siriboe, who is a struggling ex-con and single father still resentfully in love with his drug-addicted ex and mother of their son.

Consequently, we see a family pulling together even as they are pulling apart. We see the secrets and the ever-present petty jealousy and resentment. There’s a tug-of-war between tradition and modernity, between black culture and assimilation. Queen Sugar is rich on multiple levels—familial, racial, sexual, gender. For example, it challenges concepts of masculinity by showing Bordelon patriarch Ernest as a nurturer, clinging to his last moments of life just to hold his grandson one last time. There’s a lot more love in Queen Sugar than in its sister series Greenleaf,which is drenched in the Southern black church experience and set in Memphis. And it takes on even bigger Goliaths, like the plight of black farmers, and focuses, perhaps for the first time, on African Americans as landowners.

But none of these shows are wholly invested in black Southern identity. Atlanta and Queen Sugarare, but not in a preachy or politically advancing manner. Instead, both shows are centered in a sense of place. And that specificity helps anchor each narrative, though they differ substantially. Having location as a bonus character enables both shows to dig deep and tell authentic stories that revolve around multidimensional characters that bear no resemblance to the caricatures we are so used to seeing. Consequently, these people feel not only like real people but like people you actually know or could be.

FX’s Atlanta, created by and starring Donald Glover, whose family moved to nearby Stone Mountain, Ga., when he was a kid, is probably not what most people, even his own fans, could have imagined. Even though Glover is also a rapper known as Childish Gambino, his FX show is largely a result of his work playing community college student and onetime-hotshot high school jock Troy Barnes on the long-running, quirky series Community, which debuted on NBC back in 2009.

Earn, Glover’s character, is living way beneath his Princeton potential and has run out of options until an underground single by his cousin Alfred (Brian Tyree Henry), who goes by Paper Boi, offers him new hope. The journey to manage his cousin’s budding career is far from a blinged-out tale of wannabe Love & Hip Hop: Atlanta vixens, VIP sections and expensive jewelry. Instead, it gets down and dirty.

It’s distinctively black and Southern. And that comes courtesy of the all-black writers who are brand-new to television, with the reported exception of Glover. They refreshingly abandon the disposable formula that has plagued far too many black-cast TV comedies. Atlanta digs deeper, going darker than most, while maintaining the weird and quirky vibe for which Glover is known.

Almost equally important, Atlanta challenges the concept of urban being just Northeastern, as in New York or Philadelphia, or Midwestern, as in Chicago or Detroit. Even though early Southern rappers like Memphis, Tenn., icons 8Ball & MJG and, later, Atlanta’s T.I., Jeezy and, now, Future have rapped and even boasted about the South’s mean streets, the perception of the South from the outside is still more about the KKK than an AK. For many of us, the hood is still the promised-land-turned-ghettos of places like Philadelphia, Newark, N.J., and Los Angeles. For some, Atlanta remains a haven, a way out of the grind of urban life. Maybe Atlanta is arguably a better existence for transplants than natives, but it is the hardships natives face that Atlanta addresses most.

If Atlanta reveals what a lot of us don’t think the South is, Ava DuVernay’s Queen Sugar is far more familiar terrain. But even as sophisticated as some of us have become in other parts of the country, Queen Sugar reminds us that there is still some good, i.e., a sense of family and community, in the rural South. Current Columbia professor Farah Jasmine Griffin wrote of the “symbolic, almost mythical sense of the South as home” in her 1995 book, “Who Set You Flowin’?”: The African-American Migration Narrative, and that’s what Queen Sugar, whose camera languishes on the beauty of the South, seizes upon.

This is exactly what DuVernay intends, but Queen Sugar is far from naively nostalgic. Adopted from Natalie Baszile’s 2014 novel, the hourlong drama, symbolically on Oprah Winfrey’s network OWN, tweaks the book’s original story, swapping out a mother-daughter tale for a more epic one centered on three siblings, while keeping the 800 acres of sugarcane that need farming after their father’s death at the fore.

Charley, the prodigal daughter of the Bordelon clan, played by newcomer Dawn-Lyen Gardner, breezes in from Los Angeles, on the heels of her professional basketball husband’s sex scandal, and pulls out numerous credit cards to make everything right. Nova, played by Rutina Wesley, is a journalist, who is away from her roots and in them at the same time. And then there is Ralph Angel, played by Kofi Siriboe, who is a struggling ex-con and single father still resentfully in love with his drug-addicted ex and mother of their son.

Consequently, we see a family pulling together even as they are pulling apart. We see the secrets and the ever-present petty jealousy and resentment. There’s a tug-of-war between tradition and modernity, between black culture and assimilation. Queen Sugar is rich on multiple levels—familial, racial, sexual, gender. For example, it challenges concepts of masculinity by showing Bordelon patriarch Ernest as a nurturer, clinging to his last moments of life just to hold his grandson one last time. There’s a lot more love in Queen Sugar than in its sister series Greenleaf,which is drenched in the Southern black church experience and set in Memphis. And it takes on even bigger Goliaths, like the plight of black farmers, and focuses, perhaps for the first time, on African Americans as landowners.

Read the original story at The Root.